Filter by Type

Filter by Category

Filter by Size

Filter by Year

Anthony Moore

British (b. 1952)

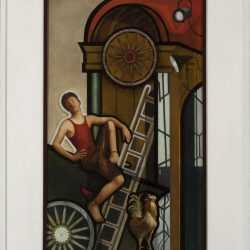

As a painting conservator and restorer with an international reputation, Anthony Moore is a master of countless historical periods and artists’ styles. That wide-ranging technical proficiency is the hallmark of Moore’s personal oeuvre, a seamless blending early Renaissance precision with perspective-challenged cubism and magical realism.

It’s as if Moore has a secret Time Machine in his studio allowing him to jump back and forth through the centuries, depicting diverse subject matter – nature, architecture, the human figure, draped fabric, heraldic symbols – through the prism of old world and modern art influences. Adding an almost mystical subtext is the compositional framework of aggressive black lines that compartmentalize images into related and unrelated fragments. At a distance, the paintings look like stained glass, but one that was broken apart and put back together incorrectly, as the images don’t quite connect.

The result is a series of highly original, masterfully rendered and altogether intriguing paintings.“When you put two incongruous things together, you have to make it possible for the viewer to make some meaning between them,” explains Moore. “If they are too disparate, there’s no meaning and it becomes silly. People shrug their shoulders and walk away. But it also can’t be too obvious or the paintings lose their otherworldliness. What works is when the viewer can decide what he or she is seeing.”

Moore’s latest exploration of collaged imagery was inspired by a recent restoration project for the Higgins Armory Museum in Worcester, Massachusetts. “I was presented with this peculiar shaped object depicting St. George slaying the dragon,” says the Maine-based artist, referring to an oblong medieval shield called a pavise. Named after the Italian town of Pavia, the four-to-five foot pavises were made from carved wood covered with lightweight canvas, then gessoed and expertly painted with oils or egg tempera. The shields were so highly valued that the skilled guild artists who made them were exempted from both tax payments and military service.

Though beautifully decorated with religious, heroic, and heraldic motifs, the 15th century wood shields were well designed for battle, each backed by an iron stake fitted into a carved gutter groove. When a soldier needed to reload his crossbow, the giant pavise could be plunged into the ground in front of him as protection from flying arrows. “The soldiers quite literally put their lives behind these paintings,” says Moore. “That’s why there are so few of them left. I put my life behind my painting. The metaphor was irresistible.”

The artist first experimented with the irregular oblong shape in small 9” x 6” studies that incorporated his signature compositional structure of subject fragments delineated by bold black lines. Interestingly, that distinctive style – so like stained-glass metal armature - was ideally suited to a painted shield, alluding to both weaponry and religious crusades.

Next came painted 27” x 13” three-dimensional wood shields, later followed by startling true-to-size pavises. In the Childs Gallery exhibit, there are five different themes explored in various sizes. “I don’t know how the paintings are going to resolve themselves when I start,” says Moore. “As they get bigger, I consider if there is some way an extra element should be put in, or perhaps one needs to be removed. An area that was quite pretty in one small study became boring when it was larger, so I completely reinvented it.”

In the case of Pavise #2, there was no human figure in the initial study: the addition of one completely changed the psychological reading of the composition, even though only one fragment was significantly altered. Introducing a nude male partially submerged in murky water under a cascading falls makes one reconsider the geometric scallops underneath as possibly metaphysical wings, with the ascending diamond-trimmed branch lines now alluding to a broken crown of thorns.

A similar transmutation takes place when comparing the small study and larger wood shield of Pavise #4. Once again a male figure has been added, this time a tiny sliver of a body dressed in contemporary white tee shirt and pants. “He’s holding a picture of a rose stem with thorns,” explains Moore. “Obviously, that lets you find your way to thinking of the side graphics as a crown of thorns. I like those thoughts. Something like a rock or the sky can metamorphose into a fabric or a stage set. I don’t want you to feel you are in a real world.”

That off-kilter uneasiness is evident in much of Moore’s works, such as the cubist tour-de-force Hever Castle (2003), which the London-born artist reconstructed from memory inserting heraldic motifs done in a collage-like abstracted manner.

More unnerving is the allegorical Sunbathing on the Tower of Babel (2000), with its startling impossible perspectives and splayed nude male figure. “That picture came about because I was looking at a knotted tie,” recalls Moore. “I was thinking of the Tower of Babel, which I’ve restored in several works, and I pulled that shape of the tie in reverse with the bricks, making the tower structurally unsound. Then I saw my stepson sunbathing in the grass and the way he was lying down looked as if he was falling off my tower. I had sort of a platform halfway up and liked the idea of reclining and falling off. In a literal way, it illustrated something of the striving and ultimate lack of success of the tower.“But it’s important to make a statement obliquely. There must be room for the viewer’s interpretation.” (Both Hever Castle and Sunbathing on the Tower of Babel are in the Childs exhibit.)

But even without the intellectually challenging subject juxtapositions – often as mysterious as they are disciplined - Moore’s paintings would demand close scrutiny because of his astounding technique. “When you’ve restored thousands of paintings as I have, you understand color in a very different way,” says the 60-year-old artist. “You put a color down then glaze over it to get the color you want. You can bring it up or down. I’m continually glazing and scraping with a blade. It took two months to get the exact blue I wanted in just one painting.”

That painstaking technique puts the contemporary artist into a category Childs Gallery refers to as “New Old Masters,” says gallery president Richard Baiano. “Tony is a meticulous painter, one of the most technically gifted I have ever seen. He builds up glaze after glaze after glaze to achieve the exact effect and color he’s after. Also much like an Old Master he starts with a jewel size study, moving up to a medium size, then quite large. He is very thoughtful and deliberate.”

Anthony was born in London in 1952. After graduation in 1974 from Exeter College of Art, he painted a series of grisaille paintings in oil on board, a selection of which were exhibited at the Paton Gallery Covent Garden London.

During the early eighties he executed a group of small portrait paintings & drawings. A solo exhibition of these works and the grisaille were shown at Mandells Gallery Goodmaynes, Essex in 1984.

He emigrated to the United States in 1987. The paintings for the exhibition “The Very Rich Moments” held at Mercury Gallery Boston, were started in 1999 and completed by 2004.

His most recent endeavor is a series of five 'pavises'. Contact us for more information or visit www.anthonymoorepaintings.com.