Filter by Type

Filter by Category

Filter by Size

Filter by Year

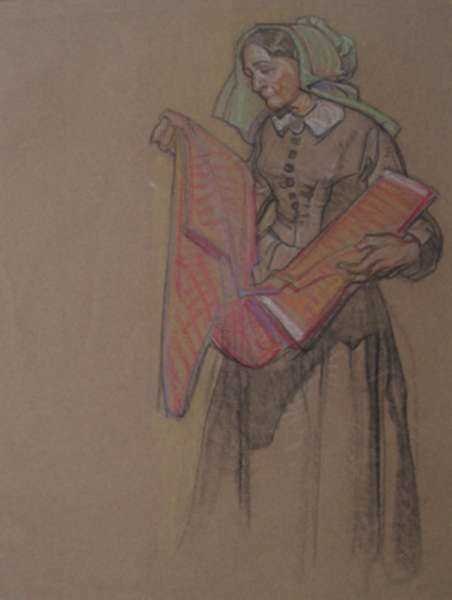

Dean Cornwell

1892-1960

For over three decades, Dean Cornwell was recognized as the "Dean of Illustrators", and was a celebrated and well-known name during his lifetime. He was widely regarded as an instructor and idolized by a generation of illustrators, lecturing at the Art Students League and at art museums and societies throughout the United States during the “Golden Age of Illustration”. His paintings were exhibited at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, the Chicago Art Institute, the Pratt Institute, the Art Center of New York City, and the National Academy of Design. Between 1914 and the late 1950's he produced over 1000 illustrations for poems, stories, and novels. Between 1920 and the mid-1950's, his illustrations appeared in magazines and posters as advertising for hundreds of products, such as Palmolive Soap, Coca-Cola, Goodyear tired, and Seagrams Whiskey. In addition to his career as an illustrator, between 1930 and 1960, Cornwell was one of America's most popular muralists. His historic murals decorate over 20 public buildings across the United States. Cornwell was an illustrator who tried to find a meaningful role in a world constantly changing with technology. His greatest inspirations were Howard Pyle, N.C. Wyeth, Edwin A. Abbey, and Harvey Dunn. Despite Cornwell's prolific and well-regarded work, today he is much less well known than during his lifetime. This trend is, however, well on its way to being reversed. The “Golden Age of Illustration” is being revived by collectors—most notably works by Cornwell’s colleagues Norman Rockwell, and N. C. Wyeth. And, after a period in which all representational art of the twentieth century was suspect to many of the most prominent critics, realism is again beginning to dominate the art scene—Beginning Again if you will.

Dean Cornwell was born on March 5, 1892 in Louisville, Kentucky to a family with a strong pioneer heritage. Cornwell's boyhood home overlooked Mile Pond, and as a result of severe headaches he suffered from as a child which prevented him from studying much, he spent long hours on the riverbank watching the riverboats pass by. Some of his earliest drawings have a steamboat theme. From an early age, both of Cornwell's parents encouraged his attempts at drawing and both complemented and critiqued his perspective and composition. Cornwell's mother taught him to observe and identify different plants and trees, which was later reflected in his illustrations of natural history.

After elementary school, Cornwell attended Manual Training high school with little academic success. He loved to draw, but as his vision began to worsen, Cornwell abandoned his hopes of an art career and joined a union as a professional musician. He had played the cornet since his youth. However, when Cornwell turned 18, he was fitted with glasses which vastly improved his sight and again began to dream of a career as an artist. He began art lessons and soon published his first drawing, The Snow Fort, which appeared on the children's page of The Courier Journal. Cornwell then began drawing cartoons of visiting musical shows for The Louisville Herald, where he was promoted to the position of full-time staff member. During this period in his life, Cornwell continued to play the cornet during the summers at nearby mountain resorts.

In 1911, Cornwell relocated to Chicago and attended classes at the Chicago Art Institute sporadically. He also returned to newspaper work at this time. He would make tracings in pen and ink over silver-prints from photographs of machinery and other merchandise. Cornwell also supplemented his income by painting scenery for window displays and drawing cartoons. Cornwell was then hired at The Chicago American, which he drew borders and made layouts for the theatrical and magazine sections. Next, he was hired as a staff artist and expert letterer as well as the illustrator for the Sunday feature page at the Chicago Tribune. These experiences form the basis for Cornwell's reputation as a competent commercial artist. Soon, Cornwell held the position of top newspaper illustrator.

Cornwell set a goal to become a New York illustrator, the pinnacle of success in his eyes. He was soon hired by Ray Long, editor at Red Book Magazine, who gave him his first magazine commission for three illustrations for the November 1914 issue. In 1915, Cornwell moved to New York and enrolled in the Art Student's League. Here he met Harvey Dunn, who invited him to participate in a three month summer school course that he and Charles Chapman were conducting in Leonia, New Jersey. Dunn and Chapman had formed this school to teach illustration as a result of their dissatisfaction with current teaching methods of most art schools of the time. Dunn's summer course taught the basic principles and beliefs of Howard Pyle, with whom Dunn had studied as a young man. Pyle had founded the Brandywine School of Illustration and inspired many students with idealism and a sense of mission in their artwork. Cornwell thought of himself as a "grand-pupil of Pyle." During this summer, Cornwell absorbed Dunn's philosophy of painting and studied the effects of light on form and tonal values. He would use these lighting techniques in his future work.

In fall of 1915, Cornwell returned to New York. In 1916, Ray Long sent Cornwell another commission for more illustrations. Long was greatly impressed with Cornwell's new and dramatic use of light and was delighted with the new tonal quality of his paintings. As a result, Long gave Cornwell commissions for Red Book short stories, a serialized novel, and stories for the Saturday Evening Post. Despite Dunn's horror at Cornwell's decision to paint advertising illustrations, Cornwell disagreed with his mentor and believed in the validity of advertising art and the fusion of fine and commercial art. During the 1920's and 1930's, Cornwell's illustrations for short stories, poems, and serialized novels appeared in Cosmopolitan, Hearst's International, Good Housekeeping, and Harper's Bazaar.

During a 1918 visit to Chicago, Cornwell met Mildred Kirkham, an editorial assistant at the Chicago Tribune. In September of that year they married and moved to a New York apartment on Broadway. Married life between them was difficult from the start, partially a result of Mildred's disapproval of Dean's enjoyment of social drinking. Cornwell soon began a series of extramarital romances, many with models who posed for his illustrations or worked in his studio. In 1920, the Cornwell's son Kirkham was born, and in 1922 a daughter Patricia joined the family. Cornwell slowly became more well-known and prosperous, and the Cornwells then moved to Mamaroneck, New York and summered in Annisquam, Massachusetts. From 1935 until Cornwell's death he and his wife lived separately but never divorced.

Cornwell worked 7 days a week most of his life. He enjoyed playing the cornet and the drum in his spare time. He was also very active in many professional organizations, such as the National Arts Club, the Society of Illustrators, the Society of Mural Painters, and the Century Association.

In 1919 and 1921, Cornwell won first prize for his illustrations of the Wilmington Society of Fine Arts. In 1922, Cornwell won the Chicago Art Institute's Award of Merit and was elected president of the Society of Illustrators. During the 1920's Cornwell decided to abandon many of the earlier Dunn techniques he had utilized and began instead to work in a more vigorous, less atmospheric style. Between 1919 and 1927, Cornwell painted in the style that established his reputation as "Dean of Illustrators."

Until the mid-1940's, Cornwell illustrated short stories and novels that served the sort of high adventure and emotion, escapist entertainment function of today's soap operas. His illustrations reflected the hopes, ideals, ambitions, and prejudices of the American people, especially of the American women readers of Cosmopolitan, Hearst's, and Red Book. For example, from 1916 through the mid-1920's, Cornwell illustrated stories of love and adventure largely set in exotic lands or on the high seas. His heroes and heroines reflected stereotypes of manliness and femininity of that time period. He also produced many illustrations of the Wild West. Then, during the 1930's and 1940's, Cornwell changed his style of illustration to follow the times and began painting in a hard-edged, literal style. His paintings of the 1940's reflect the ideals of the decade and changing standards of beauty and good looks. By the late 1930's, Cornwell's heroines were either sophisticated adventurers or helpless women in need of male protection. During the 1940's, when the wholesome girl-next-door ideal was popular, that is what Cornwell portrayed. During the 1940's and 1950's, Cornwell's calendars and posters illustrate the values and beliefs of these decades, especially the pyramidal structure of the conventional family and strong patriarchal traditions.

In 1929, Cornwell signed a contract with Hearst Publications which set out generous rates for his work. However, at the height of his fame as an illustrator, Cornwell sought immortality as an artist through a more permanent form of artistic creation--mural painting. He apprenticed himself to Frank Brangwyn in England to pursue this goal, and from this point on looked upon illustration only as a means of supporting his family.

After returning to New York after his apprenticeship, Cornwell won a competition for the chance to decorate the central rotunda of the Lost Angeles Public Library for his plan for a mural depicting the history of California, beginning with the early discoverers and ending with the '49-ers. He traveled to London to complete the murals in Brangwyn's studio and worked on them there for three years. The completed murals inspired a mixed reception upon his return.

In 1932, Cornwell completed murals for the Lincoln Memorial Shrine in Redlands, California. In 1938, he painted a series of murals for the Raleigh Room of the Warwick Hotel in New York City. In 1939, Cornwell created a mural for the General Motors exhibition at the New York World's Fair, and finally, in 1941, he painted two murals for the Tennessee State Office Building in Nashville, Tennessee. During this period of his life he worked nearly constantly on murals and served as the president of the Mural Painter's Society between 1953 and 1956. At the time of his death, Cornwell was working on a mural for the Berkshire Life Insurance Company in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Norman Rockwell has originally been commissioned for the project but had detested it and soon abandoned it. Cornwell redesigned that mural and his assistant, Cliff Young, completed it after his death.

During the last six years of his life, Cornwell lived in a New York studio apartment on 67th Street. He was assisted and cared for by his model, Bill Magner. In the winter of 1960 at the age of 68, Cornwell suffered severe abdominal pains resulting from a ruptured main artery and died.

Dean Cornwell made major contributions to the body of American art as an illustrator, though he believed his place in art would be achieved through mural painting. Cornwell proved himself to be a master of portraying the changing lives and dreams of the American people during the early to middle twentieth century.

- biographical material summarized from:

Broder, Patricia Jean. Dean Cornwell- Dean of Illustrators. Balance House, Ltd. New York, 1978.