Filter by Type

Filter by Category

Filter by Size

Filter by Year

Paul Gavarni

French, (1804-1866)

A French artist best known for his lithographs, Paul Gavarni (né Chevalier Suplice Guillaume) was born in Paris on January 13, 1804. Throughout his lifetime Gavarni produced over 4000 satirical prints for journals and fashion magazines. Both delicately witty and elegantly revealing of human behavior and character, Gavarni’s genre scenes made him one of the most important and popular nineteenth-century artists. He is often critically paired with Honoré Daumier with whom he (and other young printmakers like Jean-Jacques Grandville and Joseph Traviés) raised the status and importance of social lithography and printmaking as an art form.

In his teens, Gavarni was encouraged to draw by his uncle Guillaume Thiémet, who was also a painter. However, Gavarni was first apprenticed to an architect and an optical instruments firm because of his demonstrated talent in mathematics, and later went on to enter the Conservatoire des Arts et Métiers to study mechanical drawing in 1818. It is unclear where and how Gavarni first learned to make lithographs, although lithography had recently made its way into France, and Paris and had become an important center of production. After completing his studies at the Conservatoire, Gavarni spent three years traveling and working in the Pyreneés, during which time he also consistently produced drawings. Many of his drawings from this period would later be incorporated into his published lithographic work. Upon his return to Paris, Gavarni practiced the same method of intense study and observation that just learned in the country, becoming an urban spectator: an artist reveling in the sensory delights of a city while maintaining anonymity in the streets as he gazed and sketched. In 1830 Gavarni began publishing work in La Mode, a fashion magazine published by Emile de Girardin.

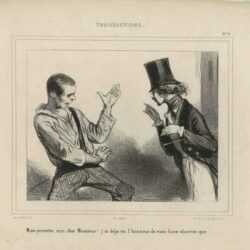

Gavarni’s success came quickly. In the 1830s he began work for L’Artiste, La Caricature, and, most importantly, Le Charivari. The latter was owned by Charles Philipon, and became Gavarni’s longest lasting contract and most important place of publication. Here Gavarni published some of his most famous series, including Les Artistes, La Boîte aux Lettres, Clichy (inspired by his month-long stay in debtor’s prison), Les Coulisses, Les Enfants Terribles, Impressions de Ménage, numerous carnival series and La Vie de Jeune Homme. Gavarni worked steadily for Philipon until 1844, producing over 900 prints, and then created eleven more series in 1846 called collectively Oeuvres Nouvelles. Later, after a three year sojourn to London, Gavarni would increase the intensity of his work and produce eighteen more series called Masques et Visages in 1852-3. Throughout this time Gavarni enjoyed success worthy of a cult figure. He was a recognized leader of the Bohemian lifestyle, socializing primarily with other leading artists and writers of the time. He counted among his friends Honoré Balzac, Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, as well as his patron Queen Victoria and his collectors Edgar Degas and Vincent Van Gogh. His life inspired two plays and his face was used for advertising. He personified the dandy, cutting a very dashing figure as he frequented late-night balls, dancing, drinking and socializing (particularly with women) and living a life of pleasure. This was the world that Gavarni often depicted in his lithographs, yet he was not a reporter. Instead, he was an acute and sensitive analyst and dramatist of social interaction and behavior.

The end of Gavarni’s career was not as publicly brilliant as the beginning. After his return from another trip to London, where he spent time observing the urban poor, he lived in semi-retirement, producing his last series in 1857-58. Much of his work from this time period is more somber, dark, nostalgic and moralistic. This is, perhaps personified by his character Pierrot (a figure influenced by the seventeenth-century comédie Italienne), who appears as a sad clown, burdened by the realities of the world while wearing the costume of a happy Bohemian in a whirlwind of celebration and gaiety. These darker realizations and disenchantments with the world turned Gavarni almost completely away from his happier fashion magazine lithographs and he became a recluse, his production dramatically declining and a preoccupation with scenes of poverty and decrepitude contributing to a drop in popularity until his death in 1866. However, Gavarni was staunchly supported by his critics (including Balzac and Gautier, Sainte-Beuve and Jules Janin and particularly Edmond and Jules de Goncourt after his death), and stands as one of the most important lithographers, both as an illustrator of modern nineteenth-century life and as an artistic innovator.

Compiled by Deborah Rogal

![Print by Paul Gavarni: Depuis que j'ai été forcé . . . [Since I was obliged . . .], represented by Childs Gallery](https://childsgallery.com/wp-content/uploads/paul_gavarni_depuis_que_jai__t__forc__._.__p194-713_childs_gallery-250x250.jpg)